I think every reader loves that moment when they find themselves captivated by their first taste of an author they’ve never read before.

Mikael Niemi is a Swedish writer whose first novel, Populärmusik från Vittula (Popular Music from Vittula), was translated into 30 languages and released as a film in 2004. While he’s authored a number of books in Swedish, sadly I could only find mention of three being translated into English, with just two of these showing up on the local paperback market. From what I’ve read online, his latest offering marks something of a change from what came before, though the synopses for his other books intrigued that hell out of me, and I have a feeling I’ll end up searching them out at some point in the not too distant future.

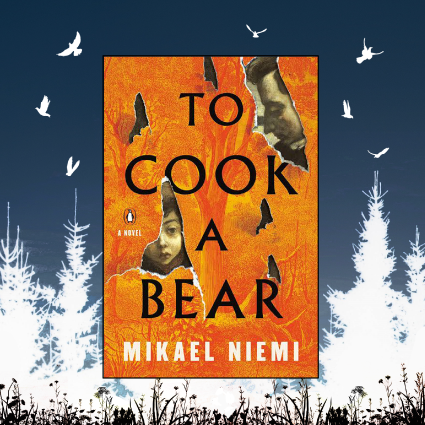

To Cook a Bear, or Koka björn, plays out in the remote community of Pajala, Sweden, in the year 1852. As leader of the Lutheran revival movement, the good Pastor Lars Laestadius has come to continue the work he started to the north in Karesuando, where his fiery sermons espousing the evils of drink have already proved unpopular with the establishment. Embraced by a community in awe of his teachings, he nonetheless finds himself once more the target of barbs from those resentful of his stance on liquor, whose complaints provide an undertow he must try to avoid as he goes about his work.

Jussi is the quiet Sami boy who lives with the pastor’s family. As with all unfamiliar things, he exists in a cloud of suspicion for the people of Pajala, haunting the pastor’s footsteps with a watchfulness that some find unnerving. Could they delve past his silence, they might catch a glimpse of the child still hiding inside the twenty year old – the grubby little runaway who could only tell the pastor he was raised by a witch – but people rarely see what they don’t want to, and there’s none so blind as the close-minded. Brought up by Laestadius like one of his own, most of what Jussi knows comes from following the man through the countryside as they indulge his passion for botany, and days spent in the pastor’s study learning to read and write.

When a young maid goes missing in the woods, all signs point to a bear attack. Honed by years spent sifting through plants, Laestadius can see that the evidence doesn’t fit like it should, but with the local sheriff resentful of his ideals he can find nobody who will listen. When a second attack is treated with a similar disdain for evidence, Jussi and the pastor are forced to begin their own investigation before the killer can strike again, unaware that as they draw closer to the truth the killer is drawing nearer to them.

The texture of this story is amazing. I love a piece of writing that makes you live in its world, and Niemi has that eye for detail that makes each scene totally immersive; so much so that the more visceral passages seemed to hit harder and linger for longer in the pit of my stomach – a feat I last remember encountering in Graham Masterton’s fiction.

Aside from a piece toward the end of the book, the story unfolds from Jussi’s perspective, and it’s a perspective unlike any I recall encountering recently. Neglected by a mother whose callousness still makes me queasy when I think about it, there’s the sense of a wounded animal about him; like a dog or cat peering warily from the safety of its kennel as it licks its wounds. At the same time, he’s experiencing the same needs as anyone else – the need for love, intimacy and the sense that his life means something – none of which are being helped by his image as the quiet Sami boy who follows the pastor around. He’s thoroughly devoted to Laestadius (who took the form of Anthony Hopkins in my imagination and refused all attempts at change), but the longing for a wife and a family of his own seem to press harder each day, weighing on his mind and affecting his behaviour in ways that aren’t always to his benefit.

As detectives go, the pair’s dynamic has a Holmes-and-Watson feel about it, with Laestadius leading the boy through the clues and encouraging him to form of his own deductions. Here, though, the location adds an element to the story which sets it apart from other crime fiction; a foreignness that makes you feel a bit like a tourist visiting some exotic location for the first time, fascinated by everything you see. In a genre that’s used to seeing killers caught using DNA matches, fingerprints and phone records, there’s also something uniquely satisfying in seeing the day won on deductive reasoning, particularly by this pair. Though the ending of the story doesn’t lend itself to it, I wouldn’t be against the author bringing Jussi and the pastor back for another investigation somewhere down the line.

Yet while dastardly deeds forms its axle, this isn’t just a crime novel. For those of us lacking a green thumb or any sort of history in biology, the pastor’s botanical jaunts make for illuminating reading, while the history of his church’s revival and its impact on the Sami people proved just as fascinating. Throughout the book I kept coming across observations about life that resonated for the truth in them; moments of simple pleasure tempered by scenes that reminded me of our species’ enduring propensity for cruelty and pain. The story has heart, but it also has a dark side, and though I loved this book there are images from it that are likely to haunt me for a while.

The character of Pastor Lars Laestadius is based on a real figure in Swedish history, whose revival movement in the 1800s is credited as being a cornerstone in the cultural heritage of Sweden, Finland and Northern Norway. According to the author’s afterword, Laestadius has found his way into a number of works of fiction over the years, though I’m not sure I could like another quite as much as I did this one. There were times I envied Jussi his friendship with the man, if only for the calm dependability of his character. In a world of constant flux, I think everyone could use a bit of that.